Another inane blog post about blog posts.

31 May 2009

I have been using a blog aggregator (Google Reader) for the past year or so, and I feel I have settled into the right distribution and quantity of feeds. In the beginning, it was quite anthro heavy, as I continued to entertain anthropology grad school fantasies. After several months, I entered a phase of heavy subscription, following links and hopping from blog to blog in a frenetic race of references and cross references. Of course, the sheer magnitude of posts and the anxiety that came with not being able to read everything served up made this untenable. As of late, however, I have found a comfortable distribution of subjects and a reasonable volume.

The first grouping of blogs (and, though I hate to say it, probably the most instrumental in getting me through the day) are first and foremost collection blogs. Rather than being polemical, chronological, or narrative, they simply (but with great relish) catalogue and collect the shinier pieces of flotsam in the internet sea. Whether devoted to fashion blunders , passive-aggressive notes , or pictures of inanimate objects that happen to look like faces, these posts celebrate the humor and irony that come with the diversity of the internet. They also tend to update most frequently, which appeals to the shorter end of my attention spectrum. The second grouping contains the veteran subscriptions; anthro-centric, polemical, and intellectual. Though some of them do a bit of collecting, they typically do so with analysis and along thematic lines. The posts are fairly long (sometimes extremely so), and often resemble academic articles. I appreciate the depth of thought in them, and they keep me connected to the lines of anthropological thought that so captivated me as an undergrad. The final grouping of blogs are of a slightly different character, and are unified not only by theme but notably by their overall style and approach to their subject matter. Thematically, these blogs deal with architecture, landscape, design, and anything in between.

The blogs in this latter grouping first caught my eye because they shared some of my more passionate and coherent interests. They also tend to use images effectively, not as stand in for text, but as a narrative component – a recognition that there is something tactile and vivid in architecture and landscape and design that cannot quite be done justice in words (and only very provisionally by images). But most importantly, they engage their topics and frame their inquiries in the same way, and it is this framing, this discursive style, that I want to really discuss.

Fundamentally, these blogs operate in a mode that explores topics not by close research but by imagination and creation. In this way, they operate rather differently than the more academic blogs I mentioned: while the anthro blogs (following standard scientific method) drill into a topic, getting ever deeper into the intricacies of the issue and the internal relationships and processes that underlie it, with the ultimate aim to understand it better and to then (hopefully) inform further action, the design blogs proceed from a phenomenon, idea, or built structure and proceed outward, imagining the thought entity in different contexts, teasing out alternative futures, and manipulating the idea in different ways. It is fundamentally a creative process, and takes cues (often explicitly) from fiction – specifically, science fiction.

Many entries begin with a snippet from the news or a set of images. Context is never too much of a focus; in fact, they generally start in the collector-blog mode, reaching down and grabbing anything that catches their cursory glance. But at some point, they introduce a twist into the situation, asking, “what would happen if…”, or, “imagine the situation if…”. In these instances, the thing or event recounted becomes a springboard to an entirely different matter, worthy of a whole new set of considerations. For example, Alexander Trevi of Pruned recounts a New York Times story about the leaks that have beset the New York City water supply tunnels, and the extraordinary challenge of repairing them. He departs from this already rather quirky story to imagine if the service crew, forced to proceed deeper and deeper through the city’s water network, tending to a never-ending cycle of repair, were to “make camp permanently.

They will live and work inside hyperbaric chambers, They will marry inside submarine cathedrals and synagogues; have children; rear them under compressive, metal-buttressed skies; drop them off to helium filled schools; develop indigenous customs, idioms and myths. They will evolve a new dialect to accommodate their ‘high-pitched squeals.’ Hydroengineering has reconfigured their biology, and so they must adapt.”

And in the ultimate reversal, “They will also die there, with their bodies sent to the surface for burial.” Of course, these scenarios are proffered with a healthy dose of humor, and are often in the mode of reduction ad absurdum.

But as with any good science fiction, the imagining of alternative futures is not done simply to be playful. It is not creativity simply for the sake of creativity; it is a pointed, directed imaginary, intended to evoke attention to an idea or concept through the process of shaking up or recontextualizing. Trevi is exploring hidden or unexplored forms of urbanism (in fact, subterranean living is a surprisingly frequent theme in these blogs. Kind of a recurrent mole-people theme.

I wish a good, conscientious director would remake The Mole People, but really take time to design the mole kingdom, how it would look, how they would harvest their life-sustaining mushroom crops, and so forth). Trevi is also making a point about urban infrastructure; grand and complex systems that are ignored until something goes wrong with them. Based on this and a number of other posts, he has a particular fascination with forgotten and invisible landscapes, and I suspect a bit of frustration at the fact that these ignored landscapes are as laden with history, beauty, and significance as the most picturesque vista, but are nonetheless marginalized as the pursuit of the offbeat dilettante.

In any case, these bloggers make their investigations by recontextualization, as a means to unsettle the current state of affairs and ask an unexpected set of questions. I see a parallel between this kind of investigation and the work done by science fiction writers. I have had a long-standing passion for science fiction, one that has evolved and grown with my other intellectual interests. Truth be told, a lot of science fiction has a rather puerile and highly gendered appeal, taking masturbatory delight in the imaginative details of technology (and often militarism) with little commentary. I feel this is more true of “hard science fiction” (although having attention to scientific detail does not preclude a work from being profound… Robinson’s Mars Trilogy is a case in point, with the character of Ann Clayborn being particularly interesting). It’s a little bit like those inane Monster Machine episodes on TLC that showcase huge machinery without any particular interest in any context about their development, predecessors, or deployment.

But there is some fantastic science fiction that uses this process of recontextualization to ask serious questions about society and the lives we lead. I think this kind of exploration can be found in a number of forms; anthropologists investigate distant cultures and end up unsettling categories of thought they had taken for granted but that end up being quite different on the other side of the world. Historians do so as well, taking seriously the line by L. P. Hartley: “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there” (yes, I have used this quote in previous posts, and you will likely find it again in the future). The finest histories, in my humble estimation, are those that attempt to illustrate the conditional and highly historically-contingent natures of the institutions and ideas we take as a given. Finally, there is science fiction, which takes familiar literary trappings – protagonists, antagonists, settings, and plots – and sets them loose in a strange and unexpected set of material conditions. Thus recontextualized, the relationships we might expect as readers are reconfigured and disrupted. An excellent example of this is the work of Ursula LeGuin, whose “Hainish Cycle” books explore themes of gender, sexual identity, anarchism and authority, and ecology (among other themes). Admittedly, the connection between her writing and anthropology is less than serendipitous… her father was Alfred Kroeber, one of the fathers of American anthropology. In any case, her interlocutors (themselves often filling an anthropological role) explore worlds in which conventions are upturned. In The Left Hand of Darkness, the protagonist encounters a race of hermaphrodites whose sexual politics and customs are determined by the seasonal transformation of gender. In The Dispossessed, we encounter a planet of anarchists, who live in a society ostensibly without coercive authoritarian structures. Even more interestingly, both of these books (and others in the “Hainish Cycle”) are set on harsh planets which challenge the characters. This interplay of environment and culture is a less-noted element of LeGuin’s work, and I think sometimes critics gloss her work as “ecological science fiction” without really dwelling on the rather complicated linkages between these harsh landscapes and the cultures that have evolved in response to them.

The point I am trying (ineptly) to make is that one of the most valuable forms of scientific investigation may in fact arise from creativity, as opposed to hard analysis. Creativity is a way of destabilizing norms, and interrogating some of the more insidious and ingrained conventions that we live by.

This is an uncomfortable notion for a scientific method that prides itself on methodological and analytical rigor. This discomfort is evident in the defenses that Anthropology as a discipline has had to raise against repeated attacks on its rigor and status as a legitimate (social) science. I stand by anthropological method, and I will sing the praises of good science fiction to anyone who will listen. I love the impetus in design to create solutions through imagination.

But, particularly where blogs are concerned, a more cautionary note is in order. There is the risk in these design blogs to give far too much priority to creation, to the detriment of analysis. Part of this may come from the overall format and spirit of blogging – this is a medium that revolves around updating, more akin to a news feed than a scholarly journal (of course, there is probably something to be said for hybridizing these forms, and rehauling the academic publications… but I digress) with the consequence that breadth is prioritized over depth of analysis.

An example of this is Bryan Finoki’s blog Subtopia. Others in the blogosphere commend him as an urban theorist and expert in biopolitics, geopolitics, and militarized space (none of which is ever really defined clearly), and he certainly makes an effort to embody these roles, complete with ponderous postings like “Peripheral Military Urbanism” or “The Spatial Instrumentality of Torture.” I cautiously agree with the notion that inequality and oppression operate robustly on the spatial plane, and I likewise agree that faith in the ability of design to positively impact the human condition must be tempered with a keen understanding of the propensity for design to amplify suffering. However, in Finoki’s indignant tirades against concepts such as “Carceral” or “Suicidal Urbanism,” there is a startling lack of interest in agency, whether by the victims or the perpetrators. There is a certain self-evidence in the evil that inhabits and animates these spaces and places. Finoki’s process is as follows: he seizes upon a news story or set of images, creatively amplifies them, and evaluates them in the degree to which they embody the monolithic, institutionalized spatial evil that he, thankfully, has the critical insight to see. As example of this is the post “Suicidal Urbanism: The City as IED,” in which Finoki departs from an Oxford study exploring links between an engineering mindset and a propensity for terrorism, and then spirals off in an imaginative scenario in which “Jihadi” engineers and developers create sabotaged cities that turn on their new tenants, acting as colossal IEDs. I think he is trying to comment on the potentiality of architecture to be weaponized, which is an important departure from the typical discussions of architecture’s ability to help and to heal. But Finoki’s wariness comes more from his imagination than any genuine analytical work. Firstly, I get the sense from the beginning of the post that he didn’t actually read the study he linked to (this is actually emblematic of a recurrent research methodology in which he googles a term or idea, finds a book on Amazon or Google Books that, according to the paragraph review or page excerpt, seems to touch on the issue, and then offers it as research on the matter). Moreover, the use of the term “Jihadi” – which is a made-up word – reflects the lack of concern for the people behind this envisioned architectural evil. It is remarkable how Guantanamo Bay, border fences, and surveillance operate so transparently in their evil, and how easy it is to elide the motives and rationales of the people who operate them. I am no friend of these institutions, but I think it is ultimately a poor analysis that fails to seek out, understand, and interpret these institutions as dynamic and subject to change (whether from without or within).

This is not simply a matter of portraying both sides of an issue, and it is not a call to justify the very serious destruction that these institutions can engender. Nor is it a call for extreme moral relativism, in which an agent’s means are justified by his/her good intentions. But the process of intellectual critique must base itself on more rigorous research methodology – research that is committed to the many perspectives that surround and inform a debate or institution.

I have spent the last few paragraphs throwing stones from the roof of my glass house, and need to draw these ideas to a close. In the blogs that I frequent, many of them do excellent thought work through the process of creative imagination – a process for which I see correlates in science fiction and in anthropology. As exciting an engaging as this process is however, it should not be permitted to stand in for close (dare I suggest enthnographic) research. Perhaps this is more generally true for design, whether industrial, urban, or of any other stripe; imagination is a potent means of interacting with the real, but it cannot stand on its own.

Is this chair certified indigenous?

12 April 2009

Update to an earlier posting!

The results of the One Good Chair competition came in, and if I had a greater attention span, I might have caught this a year ago. The winning entries are a bit dull, though the runners up are pretty cool. I particularly enjoyed Catherine Pena’s design for bus stop chairs. Simple, practical, not based on some reified notion of proper ergonomics. I think what most appealed to me was her presentation, which consisted of a few photos of the prototype in action, and a few pencil drawings :

This is such a welcome departure from the usual design boards which feature ultra-clean, computer-generated renderings with as many colors, font sizes, and unintentionally comical fake people as can be crammed on the board. Pena’s images, for all their simplicity, have warmth and craftsmanship in them. From a purely technical perspective (on which I am grossly unqualified to comment), it seems like the prototype might need to be beefed up a bit to endure more wear and tear. The design also makes it so that at least one of the two seats is facing away from traffic, making it hard to see a coming bus. You could sit facing the street, but then you have no backrest and a passing biker might graze your legs. Still, I like it.

It seems, however, that the competition will be back for another year. This time, it’s cultural.

The introduction to this year’s competition takes a very different track than the last. Suddenly, sustainability emerges from culture rather than form:

How we sit relates more to culture than anatomy, and many cultures are chair-free. Gandhi sat on the floor as a way to resist “Westernization” and honor local customs. The hammock originated 1,000 years ago in migratory cultures of Central America—woven from the bark of the Hamack tree, it traveled light, floated above the ground to fend off insects, and breathed in the humid air.

The challenge, as stated on the website, is to “design an original chair that embodies and enhances a particular place.” It should embody such things as identity of place, indigenous materials, and culturally determined notions of comfort. There is also a substantially expanded set of jurors for this competition.

I will be curious to see how explicitly entrants seek to link indigeneity and sustainability. I think this linkage a bit more complicated than is typically acknowledged. In a very mechanical sense, there are green arguments to be made for sourcing local materials for furniture. But this competition declares that a successful design “should stimulate a tangible sense of belonging to its cultural and natural context.” Arguably, that tangible belonging comes out of use rather than design. The declaration that the “low tilt of the Adirondacks Chair” emerged as a reflection of “the mountainous terrain of upper New York State” makes me laugh a bit. But we’ll find out in September. I’m hoping a couple of entrants might connect chair forms with specific historical practices, and explore that. I also hope a few of the designs are done by hand instead of tiresome 3ds Max rendering. Wouldn’t it be nice if a design was done in gouache? Or maybe clay?

You all better watch out. One of these days, I might get off my soapbox and enter one of these competitions myself…

Dana Mosque

16 March 2009

The Jordanian village of Dana, about 150 kilometers south of Amman, sits atop the edge of a plateau at the head of Wadi Dana, a valley that leads from the highlands into the Dead Sea rift valley. The valley descends from a height of 1,200 meters to 300 meters, with the village occupying a saddle of land at the top. The views down the valley are exceptional, and the village environs are irrigated by springs which drain down the valley; the upper reaches of the village are rich in orchards. The Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature manages the wadi as a nature reserve, and runs a renowned guesthouse in the old village, as well as an eco-lodge at the bottom of the wadi. In Khirbet Feynan at the base of the wadi can be found archaeological traces of some of the earliest copper mines in the world.

The village of Dana is one of the more intact of the traditional plateau villages, though other villages such as Shammakh to the south have a similar posture on the landscape. Villages of this type are found near the top of the plateau, as the land begins to slope into the rift, where the watershed meets the surface and springs allow irrigation. The architecture of the village structures consists of rough hewn stone squares with stone arches that span the width of the structure. The roof consists of reeds or branches placed across the arch tops and the exterior walls, sealed with soil, straw, and clay-like mud. The structures are close together, with narrow alleys, and infrequently exceed one story. They generally have a single doorway, and very few, if any, windows.

From the 60s on, the Jordanian government began extending services to the villages, however the terrain made infrastructure delivery difficult, and “new” districts for these plateau villages began to grow on the level top of the plateau, near major roads. Populations shifted rapidly to these new villages (the structures of which are almost exclusively inexpensive concrete block), leaving the traditional villages in disrepair. Ownership of these old village plots endures among the village families, but has become and will grow even more convoluted because of inheritance practices.

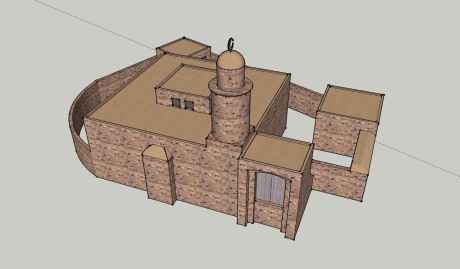

Dana, largely due to RSCN investment and tourist interest, has received considerable care, with a number of structures and the major village lanes renovated and rehabilitated. Among these structures is the village mosque, which has been restored and is a particularly beautiful example of traditional design.

I have modeled the mosque based on approximate measurements. Unfortunately, the model does not convey the immediate surroundings and terrain, which are important element of the overall architectural impact of the structure.

Perspective 1

In perspective 1, the main door level indicates the soil level, which slopes considerably. The qiblah niche is protruding from the wall. The minaret is stone, which contrasts with the corrugated metal used in newer mosques.

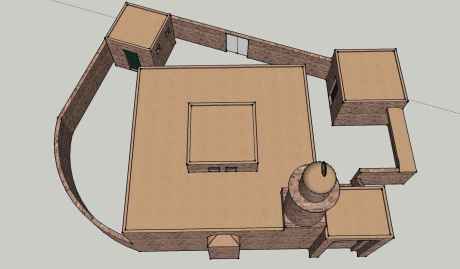

Perspective 2

Perspective 2 indicates the rear door, and a small storage structure to the right. The mosque has no windows into its main mass, but rather a set of clerestory windows at the roof level.

Perspective 3

This higher perspective gives an idea of the layout of the structure. The overhanging ledge on the righthand wall shelters the ablution area.

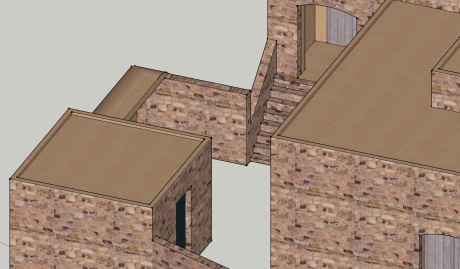

Perspective 4

The perspective focuses on the entry vestibule and interior courtyard area. Though the texture in the model is regularized, the actual stone is varied and rough.

The mosque is located at 30*40’30.98” N and 35*36’36.50” E

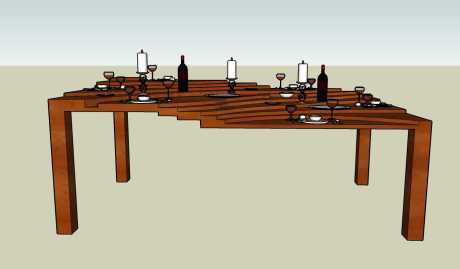

Topo Map Table

27 February 2009

This table came to me when looking at a contour line map. I have tried to accomodate place settings in the topography. The primary obstacle will be chair clearances, as the different sides will require different heights.

Perspective 1

Perspective 2

A tablecloth of suitable rigidity might smooth the levels, making for an interesting effect.

Don’t You Quote Hobbes at Me, Nature Boy

13 April 2008

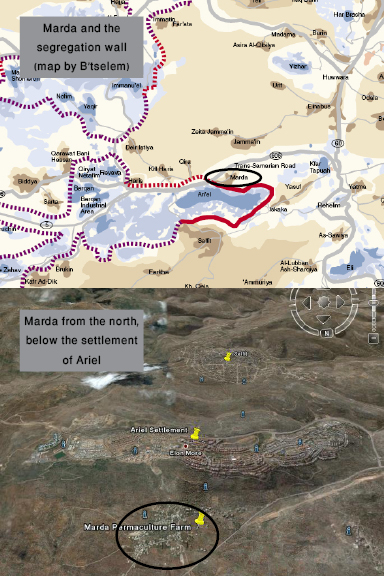

Marda is a small Palestinian village about halfway between Nablus and Ramallah, not far from the town of Salfit, nestled in the hills of the central West Bank. It is not atypical of other villages of its size, and though it has the pointed misfortune of laying in the shadow of one of the largest Israeli settlements in the West Bank, its challenges mirror those faced throughout the Occupied Territories.

It is unique, however, for being the location of an experimental permaculture farm; Palestinian owned and operated, the farm is one of the few agricultural “experiments” in the West Bank (and in the Middle East more generally) that doesn’t depend on foreign aid and a bevy of overpaid foreign specialists. I recently had the opportunity to travel to Marda in order attend a workshop on permaculture, and stumbled upon a fascinating ecological philosophy, which engages provocatively with questions of design, community, sustainability, and ethics.

The earliest seeds of permaculture were sown almost 40 years ago by Australians Bill Mollison and David Holmgren, who were searching for sustainable and self-sufficient agricultural techniques as a reaction against the rise of large-scale industrial farming and extensive pesticide use. The two realized that the issue was not merely a technical or technological one, but rather a problem that had concomitant social and ethical dimensions. The movement which resulted has sought to synthesize the agricultural and social within one philosophy, and though many permaculture specialists seem content to ignore the political elements of the philosophy, it contains within itself a firm political and moral commitment, which I think is worth exploring.

Permaculture proceeds from a number of dire ecological issues, the foremost being soil loss and the loss of biodiversity. Though commercial farming operates on a perhaps intelligible economic logic, it maintains a jarring distance from the ecological processes which characterize natural ecologies. In the interest of producing an easily marketable and commodifiable crop, commercial farms specialize in the raising of specific monocultures (a particular type of corn, a particular strain of soy bean). However, natural ecosystems are built upon the innumerable connections and energy transactions among numerous and varied life forms in proximity (i.e., biodiversity), and the fertility and productivity of such landscapes emerges directly from the comprehensive and perpetual reinvestment of energy and organism. In the absence of this diversity, fertility and equilibrium vanish; thus, monocultural agriculture must artificially maintain a growing window through the imposition of massive amounts of external “energy” – through tillage (which actually destroys soil fertility), expensive and taxing irrigation, intense fertilizer application, and extensive pesticide use. Without these investments (and often despite them), soil that is deprived of the biodiversity necessary to sustain it essentially dies, its fertility dissipated. In arid regions, desertification results, and in wetter regions, catastrophic erosion follows. According to permaculturalists, this process represents the greatest threat to humanity – the pervasive destruction of our means of sustenance.

Permaculture is primarily a design philosophy, a way of consciously arranging elements to produce a given end. Curiously, its focus on productivity and yield resonate with the driving imperatives of commercial farming, and it has no reservations against speaking of ecosystems in the language of use and utilization. Despite panegyrics to the inherent value of ecosystems, it seems to me that the underlying leitmotiv of permaculture is premeditated intervention in order to meet human needs (which seems to be a pretty standard meaning for “design”). The crucial distinction is that those interventions are inspired by the observation of existing natural systems, a kind of ecological bricolage. We see this ethos in permaculture’s forthright willingness to employ, and consume, animals in whatever configuration is most beneficial for the sustained health of the system (which causes a definite tension in the traditional alliances between animal rights activists and environmentalists), as well as in the mainstream permaculturalist’s willingness to introduce foreign species to fill whatever ecological niches might be lacking in their design. This is not meant as an outright criticism…I am accusing permaculture of anthropocentrism in its considerations, but that is not inherently problematic.

In any case, then, permaculture as a design methodology becomes a way of utilizing and augmenting the potentialities already available in the ecosystem; essentially, to work with nature rather than against it. Design techniques are based on several principles of natural systems:

– Everything is connected to everything else.

– Every function in the system is supplied by many elements (diversification).

– Every element should serve many function (redundancy).

The designer’s task is to maximize the available connections among elements of an ecosystem in order to bring out that system’s fertility. Multiple species of vegetation may be grown in close proximity to maximize certain symbiotic effects. Planting varieties of species, with different shapes, colors, life-cycles, and resistances largely precludes the necessity for pesticides. Large trees offer shade to smaller vegetation, certain types of which improve the tree’s root health. Connections may be nurtured through physical design, wherein area shapes may be molded to maximize “edges,” or opportunities for interface among organisms. Designs also strive to conserve water onsite through careful consideration of erosion patterns and contour details; thus, not only does the site sustain itself with its own rainfall, but soil damage from erosion is avoided. Additionally, the designer applies this design philosophy to architectural design. A dwelling should utilize the assets inherent to the site. Solar power, in combination with orientation, reduces energy needed for climate control. Moreover, the house itself becomes part of the overall landscape design, whereby greywater (and sometimes even blackwater) may be conserved, filtered as necessary, and used for irrigation.

There are aspects of permaculture that I particularly like. I appreciate the ease with which permaculturalists acknowledge and celebrate the historical precedence of and continued ability of mankind to productively interact with his environment (while recognizing the destructiveness of some of the later instantiations of this ability). Mankind is likewise bound to the networks of ecological connections, though with a degree of flexibility, which permaculture tries to mobilize. And, personally, I likewise appreciate the sense in which permaculture design tries to break down the boundaries between the house and the garden, and explore ways in which they can fruitfully interact with each other, such that the house can become inseparable from the garden, and vice versa.

The problem with permaculture (you’ll notice I don’t talk about something unless I have a problem with it), though, emerges when you start to talk in terms of scale. In terms of volume of sellable produce, a permaculture site does not even come close to the yield of a commercial agricultural operation on a commensurate area. Permaculturalists readily admit that permaculture cannot supply the agricultural economy as we know it today. Their response, naturally, is that our economy and society in general is fundamentally flawed, and that true sustainability is not attainable in the current configuration.

This is not a particularly novel argument, and I don’t want to weigh in here on whether or not capitalism is structurally irreconcilable with sustainability (it’s a huge and contentious debate, and I don’t have the time or competence to do it justice right now). But most permaculturalists recognize that permaculture is more than a design ethic or a set of techniques. It is not a technical fix. It is rather the material side of a comprehensive and revolutionary philosophical/political project.

As the workshop progressed, I was struck by the centrality of the motif of the house in permaculture. As Mollison writes in his textbook for permaculture, the “prime directive” of permaculture is to “take responsibility for our own existence and that of our children,” and that “we need to get our house in garden in order so that they feed and shelter us” (italics added). Moreover, the illustrations and design examples in the book overwhelmingly (if not exclusively) depict single family dwellings, surrounded by acres of effectively permaculture-ed landscape, complete with cow pasture, pond, and wind turbines. Even beyond the distressing and culturally limited romanticisation of idyllic homesteads, I think (as I have alluded in a previous post) that the “home,” conceived of as the unassailable seat of morality, liberty, and identity is distinctly problematic, and far less libratory that libertarian models would suggest.

This focus on the home is not accidental…the last chapter of the textbook departs abruptly from the more practical focus of the preceding chapters on trees, soil, and keyline irrigation. Entitled “Strategies for an Alternative Nation” (partial text available here), the chapter details a vision for alternative sociality which appears to consist of autonomous hamlets, bound together by the shared practical and ethical involvement of homesteads in subsistence production. I’m not going to criticize the vision for being a bit far-fetched… David Harvey has written persuasively about the importance of such broad, utopian imagination, and Hollison’s vision is almost faintly reminiscent of the anarchist colony Annares from The Dispossessed which is my very favorite book. But I feel that the terms of the vision, and Hollison’s explanations, demonstrate a fundamental misunderstanding of the histories and cultural practices which give our contemporary social structures meaning and significance, despite their demonstrable and myriad problems.

Firstly, later in the chapter Mollison creates an arbitrary and rather trite set of population thresholds beyond which certain forms of social life are or are not possible. Most maddening is his condemnation of urbanity, expressed in his contention that a social group of more than 10,000 people breeds crime, fear, and anti-social behavior. As someone who has studied urbanism a bit, I find this to be at odds with a substantial battery of urban ethnography that refuses to write off urbanity as a perversion, but rather explores its liberatory potential alongside the malaise. Furthermore, urbanity is not merely a spatial manifestation of late-capitalism, or an engine for lucre and accumulation. Cities existed before capitalism. Archaeology has outlined (though by no means exhausted) the complex interplay among ancient agriculture, economics, and settlement patterns such that the convenient historical narrative of hunter-gathering/egalitarian society to agricultural/hierarchical society becomes little more than a caricature. [This brings me to a particularly pointed criticism I have of the permaculture literature (and much of the environmental literature in general): a few scattered and unsubstantiated stories of romanticized aboriginal ecological sensitivity DOES NOT constitute anthropological proof of anything. The fact the Bill Mollison grew up in Tasmania, where there were once some aborigines, does not entitle him to speak for them, or to mobilize their history (which he doesn’t appear to know beyond anecdotes) for his purposes. This noble savage, paradise lost narrative of indigenous tree-hugging has been criticized by anthropologists for decades. If indigeneity is coupled with environmental sensitivity, it is a political claim to be fought for. It is not self-evident.] And, to return to the present day, urban centers continue to have complex interactions with their hinterlands and with the economic/material regimes that constitute their lifeblood (see Cronon’s magnificent Nature’s Metropolis).

In a similar vein, Mollison contends that the explosive population growth that the world is facing, and which is making issues like soil loss ever more dire, would cease to be an issue in his utopian configuration. He is parroting here the reductive and facile maxim that reproduction rates vary inversely with economic security, which is used as a truism requiring no further elaboration. However, some excellent anthropology would argue that human population growth is not purely a function of resource use and species viability, but is richly framed by cultural and discursive logics of fertility, reproduction, nationhood, etc. Mollison’s Malthusian perspective is not insightful or nuanced enough to really get at this, and consequently I have my doubts as to not only the internal coherence of his vision, but also to its wider applicability.

I also am distressed by the simplistic understanding of politics as perversion of the social order. Let’s look at a quote in a bit more detail:

The world needs a new, non-polarised, and non-contentious politic; one not made possible by those in situations that promote a left-right, black-white, capitalist-communist, believer-infidel thinking. Such systems are, like it or not, promoting antagonism and destroying cooperation and interdependence. Confrontational thinking, operating through political or power systems, has destroyed cultural, intellectual, and material resources that could have been used, in a life-centred ethic, for earth repair.

It is possible to agree with most people, of any race or creed, on the basics of life-centred ethics and commonsense procedures, across all cultural groups; it matters not that one group eats beef, and another regards cows as holy, providing they agree to cooperate in areas which are of concern to them both, and to respect the origins of their differences as a chance of history and evolution, not assessing such differences as due to personal perversity.

It is always possible to use differences creatively, and design to use them, not to eliminate one or other group as infidels. Belief is of itself not so much a difference as a refusal to admit the existence of differences; this easily transposes into the antagonistic attitude of “who is not with me is against me,” itself a coercive and illogical attitude and one likely, in the extreme, to classify all others as enemies, when they are merely living according to their own history and needs.

Mollison makes the same movement that the Archbishop made so many posts ago. In subordinating difference to some cultural garnish to the natural main dish, he refuses to take difference seriously. He doesn’t deny difference; worse, he trivializes it. Cultural difference results merely from the “chance of history and evolution,” and if we all could just understand our shared, biological need for sustenance, we could base an apolitical polity on it, and dispense with the tiresome politics of difference. Of course, permaculture, like other environmental rhetorics, professes an attention to difference, insofar as it frequently and readily utilizes indigenous conservation techniques. Alliances are often forged between environmentalists and indigenous peoples’ movements. I am not accusing them of necessarily being infelicitous or disingenuous, but I think it is something of a marriage of convenience. Permaculture gets to decontextualize and harvest the indigenous technologies of other cultures. Permaculturalists in Jordan can wear kuffiyyas and talk about Nabatean irrigation. But they have allowed themselves to avoid any experience with fundamental alterity.

The demonization of the political (which I am provisionally connecting to a notion of colliding difference) seems to be a substantial element of the permaculture ethic. The workshop was taught by a Canadian couple working on a project in Jordan (which I hope to visit), and while I did not for a moment doubt their technical competence, I was struck by their constant refrain that they were against “politics.” As one of them remarked, “I don’t talk politics.” But as I have tried to demonstrate, by talking about populations, about urbanism, about ethics, about human needs, by trying to bring about profound structural change, you are doing politics. Moreover, as I found in my research in the West Bank, the ability to claim environmental sustainability offers tremendous political purchase in the global community. Interestingly, a common criticism of Israeli settlements is that they use exponentially more water and produce far more waste than the surrounding Palestinian communities. But I have often wondered what would happen if the settlers were to embrace permaculture, and transformed their illegal settlements into paragons of sustainability? Would the already fairly weak international criticism of the settlements be weakened further? Permaculture matters politically, whether or not it realizes or acknowledges it. This ignorance of one’s own politics, of one’s own contingency, blinds one to the limitations and assumptions of one’s vision.

This point was driven home for me in the last day of the workshop, in which the reins were handed to guest lecturer Jan Bang, an aging Nordic hippie with decades of experience founding and working on eco-villages throughout the world. In our last session, we were given the opportunity to set the topics to be addressed. One of the Palestinians in attendance, having sat though days of design techniques and practical considerations of permaculture asked a simple but crucial question: How is this economically viable? Jan launched into a detailed explanation of the LETS (Local Exchange Trading System), in which existing permaculture hamlets might trade via local, currency-free exchange networks, supplementing existing currency systems. As interesting as such a system may be (and frankly, it’s not really interesting at all), it completely misses the point of the question, and fails to answer or even address it. My research into and experience with the imbrications of water and Palestinian nationalism suggested to me that agriculture figures quite large in Palestinian imaginings of nationhood, and food production is a fundamental marker of national sovereignty. I imagine that Mollison and Bang would argue that the paradigm of the nation-state is fundamentally flawed, and inherently supports environmental abuse. However, I find this to be out of touch not only with the complexities of the nation-state, but also with the realm of possibilities open to Palestinians. If permaculture does not persuade, it is not because the listener is somehow infantile, unimaginative, and unready for change, but rather because permaculture is unable to meet the needs of the world as it functions. In that respect, I feel that permaculture often entails a peculiar reclusion from the outside world.

It is important to realize that permaculture is by no means a monolithic and stable movement, but has experienced a degree of fission and friction. I only had access to Mollison’s textbook, though I’m told that David Holmgren has written about urban permaculture at some length (and, honestly, from what I have heard, Mollison isn’t exactly the brains of the pair). I also do find the practical logic of permaculture to be engaging and enlightening. It is also a robust criticism of commercial agriculture. But the movement to human sociality is far from straightforward.

[Incidentally, this is not about Jordan. Not even a little.]

I came upon a call for a design competition entitled “One Good Chair.” You can check out the details yourself if you like (or enter the competition, if you’re a tool, er, up for it), but I’ll sum it up.

The competition is to design a “new kind of eco-chair” (as opposed to the old kind, I suppose), one that focuses on form, first and foremost. What shapes can minimize resources while maximizing comfort and enjoyment? How can design integrate ecology and ergonomics?

This is something I’ve been thinking about on and off for a while now; whether or not designs inherently possess certain characteristics. A more specific question would be, are technologies, in and of themselves, political? The question is not whether certain technologies can be used for political ends, which is fairly clear. Rather, do certain technologies, by their mechanics and physical configurations, necessarily entail or presuppose, or perhaps are just “strongly compatible with,” certain political configurations? This is a question pondered by Langdon Winner in his 1986 book The Whale and the Reactor, and while the age of the book precludes a discussion of the internet, which is arguably more germane to the question of political technology than the issue of nuclear power which seems to be the main thrust of the book, it is still a fantastic attempt at developing something like a philosophy of technology.

As Winner relates, Engels, in one of his rebuttals of anarchism, cites the inevitable authoritarianism that arises from the material conditions of our production, even after the revolution (Marxist materialism’s hard-line towards technology also interestingly popped up in Soviet perspectives on environmentalism…I’ve found some nifty sources for that, and I hope to post on it some time soon). This is an echo of the much older argument in Plato’s Republic that ships, by their nature, demand the steady hand of a captain as well as the concerted and coordinated labors of a subordinate and hierarchical crew. Of course, these arguments beg the question of the naturalness or inevitability of these configurations, and, at least to me, suggest a certain poverty of imagination of how alternative technics might operate. I seem to remember David Graeber reflecting on anthropology’s extensive documentation of a staggering variety of cultural responses to subsistence, from the starkly egalitarian to the rigidly hierarchical, often within close geographical proximity.

In any case, it seems that we get caught up in the dialectic between an argument for objective realism (the physical reality of the technology is self-evident and we react to it as to an objective fact) and an argument for social determinism (technology lacks any inherent meaning apart from that which we socially impart to it… if we don’t see the tree fall, it doesn’t exist). Winner perceives both as problematic, though I think the latter is perhaps less so than he assumes. Anthropologists work a lot with artifacts – our fancy word for any kind of stuff that gets worked on/constituted by culture, which, um, I guess is, um, everything (I am already leaning toward the social determinism with that one) – and are quite keen on this dialectic. I will admit that there is a certain facile seduction in the postmodern notion that the world of things has no real existence outside of our perception and social categorization of those things (of course if you tell that one to someone in one of the “hard sciences,” they might spit on you). And I will also admit that, as Winner points out, such a perspective can easily lead to the dismissal of the artifact (be it an adze, a ship, a chair, a nuclear reactor, or the internet) as epiphenomenal to the “real,” social stuff going on. Consequently, it is easy to overlook the ways in which technologies not only are constituted by the social, but turn around and do some constitutin’ too. But I think the key point is that this re-constitution, this creative spark that an artifact can set off in a social tinder box, is not predictable, constant, or uncontested.

There is perhaps a parallel in the study of the human body which, according to the Cartesian mind/body dualism, is something of an artifact in itself. Students of gender like Judith Butler have sought to decouple the logical homology between (biological) sex and gender, suggesting that the social construction of gender, of masculinity and femininity, are not determined by biological sex, but rather are built and sustained through social discourses and practices of gender. The point is not to deny the importance of the body, or to trivialize biological difference. Rather, I think it is important to see the body, and the material in general, as something of a garden of differences-in-waiting…the human body does indeed boast sexual dimorphism, but the terms of that difference, and its significance for human-being, must be developed, indeed, sustained through unremitting discursive and practical interaction. And crucially, the terms of that difference are not contained within or prefigured by the material.

Talking about the body allows us to start returning to the question of design, since architectural design, for example, must (unless it is entirely textual and absurd) at some point acknowledge the physicality of the human form that will (hopefully) ambulate through its created space. Many architects, in my experience, love to ground their work in the eternal, universal human form. The design of spaces, then, becomes the search for spatial vocabularies that in some quasi-mystical (and generally, poorly-explicated) way resonate with the unchanging human form.  Louis Kahn, for one, expressed this sentiment in his notion of “monumentality:” a spiritual quality in a building conveying a sense of eternity, of timelessness and of unchanging perfection. Though this quality remains enigmatic, it seems to reside in a certain spatial vocabulary: “the basic forms of the vault, the dome, and the arch continue to reappear,” throughout architectural history, but with added powers of contemporary technology and engineering. In willful rebellion against the International Style prevalent at the time, Kahn emphasized his appreciation for architectural history…well…Italian architectural history, which he confused for universal human history. The lessons he learned from that history are radically different than the lessons I would take from such an experience. As Kahn wrote, “History is that which reveals the nature of man. What is has always been. What was has always been, what will be has always been.” I proceed a bit differently. One of my favorite quotations is from L.P. Hartley: “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” This perhaps explains the methodological and theoretical affinity between anthropologists and historians – the work of understanding the past is similar to the work of understanding foreign cultures. Anyway, if a spatial vocabulary (namely that of imperial Rome) recurs through architectural history, I find it a bit of a stretch to assume that is because that vocabulary contains within it a natural affinity with the human form, or with some universal human experience of space. Maybe we should think about the potential for the expression of the symbolic power of empire through classical forms. Think of architectural vocabularies as embedded within bounded fields (in the Bourdieuian sense) of value. I’m getting away from myself here, but the point is that architectural forms, I think, do not possess an inherent timelessness, or unqualified affinity with some external universal. Architecture is a garden of difference-in-waiting.

Louis Kahn, for one, expressed this sentiment in his notion of “monumentality:” a spiritual quality in a building conveying a sense of eternity, of timelessness and of unchanging perfection. Though this quality remains enigmatic, it seems to reside in a certain spatial vocabulary: “the basic forms of the vault, the dome, and the arch continue to reappear,” throughout architectural history, but with added powers of contemporary technology and engineering. In willful rebellion against the International Style prevalent at the time, Kahn emphasized his appreciation for architectural history…well…Italian architectural history, which he confused for universal human history. The lessons he learned from that history are radically different than the lessons I would take from such an experience. As Kahn wrote, “History is that which reveals the nature of man. What is has always been. What was has always been, what will be has always been.” I proceed a bit differently. One of my favorite quotations is from L.P. Hartley: “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” This perhaps explains the methodological and theoretical affinity between anthropologists and historians – the work of understanding the past is similar to the work of understanding foreign cultures. Anyway, if a spatial vocabulary (namely that of imperial Rome) recurs through architectural history, I find it a bit of a stretch to assume that is because that vocabulary contains within it a natural affinity with the human form, or with some universal human experience of space. Maybe we should think about the potential for the expression of the symbolic power of empire through classical forms. Think of architectural vocabularies as embedded within bounded fields (in the Bourdieuian sense) of value. I’m getting away from myself here, but the point is that architectural forms, I think, do not possess an inherent timelessness, or unqualified affinity with some external universal. Architecture is a garden of difference-in-waiting.

Much in the same way, I am unable to countenance the idea that architectural forms are inherently political. They can be used politically to invoke authority, or in projects of nation-building, but such a use is dependent upon memory, and discourses of what is natural, what is modern, etc. And most importantly, it is a slippery and dangerous use, which requires constant and active upkeep to sustain it against challenge and subversion.

Given this, the remarks of a pair of rather heavily-esteemed and lauded architects become a bit absurd. Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron (who in 2001 won the Pritzker award, which is sort of like the Nobel Prize for architecture) recently spoke about the potential for their Olympic stadium design in China to…um…free the Chinese by giving them multiple entrances, I guess: “The very architecture – an open basket or ‘bird’s nest’ of girders in which visitors can choose their own, random paths, is pointedly designed. ‘We wanted to do something not hierarchical, to make not a big gesture as you’d expect in a political system like that,’ de Meuron says, ‘but [something that for] 100,000 people [is still] on a human scale, without being oppressive.’” I have no doubt that the two are acting in good faith, and very well may believe that their architecture has the power to spread democracy (I suppose a bit like how a poor hospital design can spread tuberculosis). But their explanation hinges upon the assumption that a design can be inherently democratic, which, as I have endeavored to show, is nothing more than an unfortunate assumption. Moreover, it demonstrates a startling inability to understand the ways in which people produce and consume (social) space.

Given this, the remarks of a pair of rather heavily-esteemed and lauded architects become a bit absurd. Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron (who in 2001 won the Pritzker award, which is sort of like the Nobel Prize for architecture) recently spoke about the potential for their Olympic stadium design in China to…um…free the Chinese by giving them multiple entrances, I guess: “The very architecture – an open basket or ‘bird’s nest’ of girders in which visitors can choose their own, random paths, is pointedly designed. ‘We wanted to do something not hierarchical, to make not a big gesture as you’d expect in a political system like that,’ de Meuron says, ‘but [something that for] 100,000 people [is still] on a human scale, without being oppressive.’” I have no doubt that the two are acting in good faith, and very well may believe that their architecture has the power to spread democracy (I suppose a bit like how a poor hospital design can spread tuberculosis). But their explanation hinges upon the assumption that a design can be inherently democratic, which, as I have endeavored to show, is nothing more than an unfortunate assumption. Moreover, it demonstrates a startling inability to understand the ways in which people produce and consume (social) space.

And so we can now return to the original issue of the chair competition. One of the judges wrote a book which is considered the authoritative work on the “history” of chair design. A review of the book exclaimed the following:

“The radical notion put forward by a new breed of ergonomic designers that chair design…should not be restricted by ‘traditional cultural expectations.’ They want to change traditional workplace design. For them, the beginning and end of design should be the body.”

The implication here is that the ergonomic needs of the body are universal, and that the cultural epiphenomena that have (needlessly) dressed up our chairs for millennia are finally giving way to the rational, scientific knowledge of what is naturally appropriate for our bodies. But, again, I would argue that the body is much less a knowable object than a collection of innumerable contours, gradients, and differences, which are seized upon to the carry the emblems of culture, and the ergonomic is merely one system of ordering the body among many.

Given this, I cannot imagine a perfect chair. I cannot imagine a chair that is universally appropriate to a body which is constantly made, unmade, and remade in historically, geographically, and culturally specific ways. I cannot imagine a chair that is inherently good for the environment [this is another dimension of the question whether technologies are political… can a technology be inherently green? I’ll deal with that in the next post, I hope.]. The perfect “form” does not and cannot exist.

But this post is so long and boring already, I might as well dream up a few chairs, just for the hell (or futility) of it.

- The Bone Chair: A chair made of human bones. What better to address the needs of the human frame than a human frame! And humans are certainly renewable… zestfully so. Designer Joris Laarman has a less macabre version:

Joris Laarman's Bone Chair

- The Cactus Chair: It’s a cactus. Because you should be out biking or gardening or something. And it’s sustainable because it’s a friggin’ cactus.

- [ ]: Sitting shall not be commodified or abstracted from its context. Window ledges, nooks, sturdy shelves, logs. Look for the places already in the built/natural environment that invite sitting. And this chair is the true eco-chair: it doesn’t have to be built, because we already have plenty of places to sit.

I like the last one the most. But the $4,500 prize is intended to support the fabrication of the winning design, so I guess it wouldn’t work. Too far out there, suggesting we actually sit on the chairs we already have.

I spend a lot of time with architects here in Amman. In fact, apart from alone-time (which consists largely of anxiety over my lack of consistent posting to this neglected blog), I spend nearly all of my time with architects. Some of them are very well established regionally, others are months out of architectural school, and many others are somewhere in between. I read wide-ranging architectural monographs that track individual architects’ careers. I see conceptual designs being launched, and meticulous detail work being applied to final designs. Photoshop layers, CAD vectors, and 3DSmax objects promiscuously mingle and are eventually turned into buildings.

And yet, as an anthropologist mired in design processes, I sometimes feel that architectural design suffers from a tenacious myopia in which “design” as praxis becomes abstracted from the social context which precipitated it, and which it is ostensibly supposed to serve. (I’m also interested in the genealogy of thought which could have allowed design to become an isolable entity, a practice. Maybe, something like the Foucauldian archeology of the subject which seeks the development of the “madman,” “homosexual,” or “criminal,” but for the “designer.” I’ll add it to my list of PhD theses to complete). And I’m not just talking about the work of Zaha Hadid and others who are quite forthright about their iconic and sculptural, experimental, art-for-the-sake-of-art contributions to architecture, but also about those who are more committed to integrating social factors into the design process. I find that the design process can very rarely, if at all, shake off the detritus of the insular, inward-directed design studio. I don’t think it is a matter of brute narcissism, but something more fundamental to the craft. Perhaps it has to do with the privileging of the visual over the narrative in architectural design. In any case, it bothers me, and makes the chances of me ever going down the design path myself ever more remote.

But that’s not what I really want to talk about. The point is that the work of largely non-profit groups like Project for Public Spaces is something of an antidote to this design tyranny, particularly when they remark that: “Parks, plazas and squares succeed when people come first, not design…and…Making great public spaces the norm rather than the exception depends on introducing policy-makers at all levels of country, state, and city government to new ideas and approaches.” Well, it should be the antidote. I mean, this work seeks to foreground the intersection of everyday practice, the public sphere, and place. And heck, I’m interested in all of those things! It’s like a slumber party with De Certeau, Warner, and LeFebvre! And I’m invited! (Jane Jacobs is there in spirit, but she’s a girl and no girls are allowed at a guys’ slumber party…not my rules).

But more often than not, I am not entirely persuaded, and I end up feeling disappointed with myself, really wanting to get 100% behind this pro-public space urban planning movement, but always hitting a wall. Of course there is a good chance that my college education has warped me into always being armed with a critique, never being able to totally get behind anything. But maybe my unease has come from something real.

Maybe it came, like most of my clothes in high school, from Easton Town Center. Download a map! (If you visit Columbus, OH, be sure to sit a spell and enjoy the fountain at the Easton Town Square, between the Banana Republic and the Ann Taylor). It was one of the first of its kind – a shopping center modeled on the premise that the classic American main street, with its public spaces and metered storefront parking, is a nurturing paradigm for hyper-consumption. Safe, pedestrian oriented, open to the sun and sky, and well-surveilled (god help you if you are under 16 and on your own after dusk).

Okay, so this is not a fair criticism of those who are pushing public space. They would recoil even more than I at the private-sector perversion of their beautiful vision. But what is their vision? How do they propose it functions? What urban ills does it address, and how? And why, dammit, does it not impress me?!

There’s no reason to rehash the mission statement of the PPS, or any of the handful of similar organizations that have similar aims; indeed, they have websites. But I did have the good fortune to join a workshop in Amman back in November, sponsored by the Center for the Study of the Built Environment (CSBE), which sought to introduce young Jordanian architects to the mechanics of public space and their applicability in Jordan. Lead by Professor Christa Reicher of the University of Dortmund, who herself is responsible for two apparently quite successful public space rejuvenation and development projects in Germany, we were given a whirlwind survey of the nature, history, and importance of public space. Apparently, public space, which perhaps has historically found its most iconic instantiation in the piazzas of 15th century Italy, essentially affords openly accessible places for social interaction. These two elements are crucial; roads are openly accessible, but obviously unsuitable for social interaction. The private residence, shop, or mall (or Easton Town Center, for that matter) may host social interaction, but they are by no means openly accessible to all.

It seems upsetting to me that this basic typology warranted so little deconstruction. I immediately think of online communities, which afford robust social interaction and profoundly open accessibility (of course, online communities require a modicum of technical competence and hardware investment… but I question the homologousness between “no blacks allowed” and “no n00bs allowed”). It seems that a lot of assumptions are being made, not the least of which is that true, civically meaningful interaction must be face-to-face, embodied, and ambulatory.

Jane Jacobs, in her monumental study of American communities, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, made a similar assumption. Well, she made a lot of assumptions. And don’t get me wrong, it is very much a classic. I adore that the urban planning world could have been turned on its head by a woman with no formal design or planning education, and that the power of her work could emanate not from a mastery of technical arcana, but rather from her embodied experience. I adore the devaluation of the technical in lieu of the common sensical. Less science and more humanities. Less AutoCAD, more flea market. But in any case, her analysis echoes the work of urban sociologists like Elijah Anderson, who in turn depart from Goffman’s work on ‘footing,’ all of whom take an interest in the small embodied cues that, arguably, constitute the essence of social interaction. In these cases, the social dynamic is shaped by the movement of the body. Though Anderson is more sensitive to the very fine bodily cues that organize racial space, Jacobs is primarily concerned with the movement and mixing of bodies through space. Part of her work (and I don’t have the book with me so I’m going off of memory here. But you ought to read it on your own anyway because, for all of its flaws, it’s neat), for instance, deals with visibility and the conditions by which the spatial organization of bodies (specifically, around a street) allows for communal surveillance and community regulation. The ease with which bodies can circulate determines the health of a space.

And so, public space which facilitates the sustained movement of people, whether by retail, aesthetic allure, or the self-amplifying draw of people-watching, engenders healthy, self-regulating communities. Communities are organisms. (Organisms? Them’s fightin’ words…)

To get back to the workshop, as Professor Reicher’s presentations went on that day, the implicit logical progression seemed to be (and though I am being a bit sassy here, I am not misrepresenting the gist of the explanation):

Public space → social mixture → democracy/commerce → a happy, harmonious life

Once this was established, the rest of the workshop (the second half of day one and all of day two) was devoted to design techniques and strategies to build public spaces. I was left horribly unconvinced, and became downright fidgety. The presence of public space leads to greater social admixture? I suppose in a mechanical sense that is true. But this facile little movement fails to comment on how quietly but determinedly normative these spaces are. That, for me, was a crippling fault of Jacobs’ work, for instance. As much as she would like to construe her self-surveilling communities as organic and “healthy,” they fundamentally operate on processes of inclusion and exclusion. And while it is a pleasant fiction to believe that the healthy community is excluding only the most dastardly, criminal elements, while including everyone else, I think it is indeed a fiction. At one point, Jacobs, in a particularly parochial and anachronistic gesture, decries the presence of a dance club in one of the communities she illustrates as a failing community. “Healthy” communities are excellent for those who enjoy chit-chats with the owner of the corner store. They are not good for people who like to dance, or who tire of the tight-knit, everyone-knows-everything-about-everyone small town set up, or who don’t like it when the neighbors’ eyes follow them down the street. They are not good for people who do not have families. Who are homosexual. Who are politically radical.

In Amman, there is a social group, essentially teen-age boys, called the shabab, who are systematically excluded from most quasi-public space areas. Now, I won’t deny that the shabab can be annoying, immature, and raucous. Sometimes they’re just plain assholes. But one must ask just how much of their behavior is the innate irascibility and ruffianism of male adolescence, and how much results from their systematic exclusion from all of the even halfway interesting places in Amman, which is, frankly, a pretty boring city. Amman sorely lacks public spaces, and the hippest place to hang out is Mecca Mall, a mammoth shopping compound that is “family friendly,” i.e., exclusive of shabab. Again, here lies my ambivalence for the public space discourse: truly, Amman suffers from the lack of easily and freely accessible public spaces. This needs to be acknowledged and addressed. But the “freely accessible” part is constantly being curtailed and circumscribed in the planning discourse. The consensus of the young Jordanian architects was that the barometer of a healthy public space in Amman is whether or not a space is comfortable for women and [engaged] couples. Anti-shabab, and heteronormative. Public space may lead to social mixture, but it is a very prescribed mixture.

This rupture in the public space progression hints at further fissures. I am also not convinced that social admixture leads to democracy. As I noted above, I think any kind of truly kind of open mixture, which presumably is a prerequisite of the democratic process, is simply not possible (and indeed, perhaps not even sought after) in the current public space paradigms. Furthermore, there seems to be a notion, echoed in some of the publications of the PPS and in the workshop, that the physical proximity of people naturally and unproblematically leads to some kind of emotional empathy. There is a breathtaking belief (I think it is one of the core beliefs of multiculturalism, or at least cosmopolitanism) that contact breeds accommodation. That if we surround ourselves with [generic] variety, we will come to embrace [generic] difference and march off into the [abstractly] democratic and inclusive sunset. Or, on the economic side, that the mixing of the wealthy and the poor in a single space can bridge the growing gap between the haves and have-nots. This is at best naïve, and at worst horribly ignorant. As I tried to illustrate in my last post, the limits of multiculturalism cannot be elided, and there are lines of otherness that cannot be crossed. Nearness does nothing to temper any feelings of fundamental alterity.

It seemed to me at the time, and still does, that these problems were glaring and demanding serious reflection. But they were not touched upon. The architects threw themselves with gusto into the design process, creating very aesthetically appealing (though somewhat monotonous) boards, using a variety of different color markers, and a nifty technique for making appropriately abstract yet stylistic foliage. One young man poured his very being into the creation of, admittedly, rather attractive lighting fixtures to grace the public space his comrades were conceptualizing. The technical competence of the architects was beyond reproach, and despite the monotony of the format, the drawings were of professional caliber. But in the end, the architects were as they were expected to be: fine draftsmen. Whether it was “design” is certainly debatable.Undoubtedly, Amman suffers quite seriously from the dearth of public spaces. And I don’t want to get mired in the whole “well islamic architecture is more inward looking and anyway historically Islamic cities have not formed the civic structures that in the West paved the way for a finely developed civil society” debate; the fact is that Amman is not a Mamluk fiefdom, but a contemporary, increasingly globalized, world-class city that cannot but suffer from an underdeveloped spatial repertoire. Traffic is a scourge as it is in any other sizable city; yet Amman is hideously inhospitable to pedestrians. If designers were more inclined to think about these things, perhaps good changes might emerge in the Jordanian urban fabric.

And that is where I end up. Designers can make small fixes. They can intervene productively and positively on the small scale. They can be consummately skilled problem solvers. I say these things with complete sincerity. But I am profoundly unconvinced that designers can solve the larger societal ills that are only partly and opaquely manifest in the urban structure. In fact, and this needs maybe a lifetime of research and contemplation to adequately address, I wonder if the very essence of the “designer” as s/he functions in the current world order in fact precludes the kind of radical transformation of which many designers believe themselves capable.

Perhaps the discourse on public space bothers me because it does not problematize or culturally contextualize the connections between space and social life. Frankly, I feel bad about the whole matter! Urban planning is one of the few paradigms for large-scale societal intervention that takes an interest in the social and cultural. It just does it so half-assed sometimes. Hence, I think, my ambivalence.

“Sharia-Lite”

19 February 2008

I am noticing that I ironically have been following English language news more closely than I ever did back home. Which I suppose speaks to the extent to which the act of reading/watching the news is foremost a matter of consumption (as opposed to fact accumulating or self-edification). Perhaps the New York Times is filling a gap that, say, Cinnamon Toast Crunch used to fill (and yes, I know that I can find imported cereals in specialty shops, but it’s expensive, and I prefer that my cereal not be better-traveled than myself).

In any case, there has been a spate (at least in the British press) of stories that deal, on some level, with the unhappy collisions of Islamic culture with European secularism. In one instance the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Rowan Williams, recently brought upon himself all kinds of venom and vitriol when he remarked in a lecture to the Royal Courts of Justice on 7 February 2008:

In any case, there has been a spate (at least in the British press) of stories that deal, on some level, with the unhappy collisions of Islamic culture with European secularism. In one instance the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Rowan Williams, recently brought upon himself all kinds of venom and vitriol when he remarked in a lecture to the Royal Courts of Justice on 7 February 2008:

My aim is only, as I have said, to tease out some of the broader issues around the rights of religious groups within a secular state, with a few thoughts about what might be entailed in crafting a just and constructive relationship between Islamic law and the statutory law of the United Kingdom.

And later, he suggests that

If what we want socially is a pattern of relations in which a plurality of diverse and overlapping affiliations work for a common good, and in which groups of serious and profound conviction are not systematically faced with the stark alternatives of cultural loyalty or state loyalty, [accommodation] seems unavoidable.

Of course, a cacophony of voices dissented, exclaiming that an extra-judicial judiciary would abrade the very core of the British justice system, a system of one supreme law to which all are equally subject, a system which is construed as a veritable cornerstone of democracy. That word “unavoidable” was bandied about, as if uttering that single word was a sufficient alternative to actually reading the lecture in its entirety. My favorite criticism (I can no longer find the article) is from an MP who suggested that perhaps the Archbishop would be better suited to an academic environment, where those “types of ideas” can be batted around, rather than as the spiritual leader of a major denomination. The university as a sort of sanitarium, maybe.

There is a temptation to see the row as a battle between xenophobic European nationalists and those committed to an enlightened multiculturalism. This is perhaps disingenuous; I have no doubt that many of those who found themselves upset by the archbishop’s comments are hardly xenophobic, let alone racist. And yet I do think that the archibishop’s words were largely paraded out of context (which he maybe should have foreseen). But in any case, I am less interested in trying to decide which side of the debate is right. Certainly, I think it would be interesting to see some serious research on just how destabilizing such an institution as Sharia would be. Perhaps that research would profit from a more incisive look at the singular multiculturalism (or perhaps a better word is porousness) of Islamic empires through history. But beyond this, I think the debate itself, regardless of which side is right, is more interesting for what it says about multiculturalism more broadly.

Beyond anxiety over the integrity of the British judiciary, and beyond fear of the dilution of British identity, I think the fear of the Sharia is founded upon the perception that it is fundamentally unsympathetic to minorities, particularly women. It is on some level savage. Crucially, it represents an alterity beyond that which the multiculturalism of the liberal nation is willing to accept. I think it illustrates (regardless of whether this characterization of the Sharia is accurate or not) the fact that the multicultural regime, far from being ultimately permissive and welcoming of cultural difference, is rather interested in that which is palatable to the regime itself. Moreover, this arrangement requires the performance of clean and essentially innocuous difference in ways that are intelligible to the multicultural society. Just how Muslim would one have to be in order to get to use the Sharia courts? As the archbishop has reiterated throughout the escalation, the Sharia would in no way contradict British common law, or absolve those who might be held guilty under it. As he explicitly notes in the original lecture:

If any kind of plural jurisdiction is recognized, it would presumably have to be under the rubric that no ‘supplemental’ jurisdiction could have the power to deny access to the rights granted to other citizens or to punish its members for claiming those rights.

What is implied is that no part of the Sharia that could conceivable disenfranchise women will be entertained (and I really do think the gender angle is important; gender is the lens through which Islam is most vigorously criticized, which I think is evident in the disproportionately vociferous arguments over headscarves). For one thing, there is something questionable, if not darkly amusing, about a multiculturalism that insists on “Sharia-lite.” More interesting, however, is the sense I get that the multicultural, liberal society (ostensibly advocated by the Archbishop) does not merely tolerate other cultures, but rather expects those cultures to be performed in the public sphere in a way that is palatable to the sensibilities of the tolerant society.

What is implied is that no part of the Sharia that could conceivable disenfranchise women will be entertained (and I really do think the gender angle is important; gender is the lens through which Islam is most vigorously criticized, which I think is evident in the disproportionately vociferous arguments over headscarves). For one thing, there is something questionable, if not darkly amusing, about a multiculturalism that insists on “Sharia-lite.” More interesting, however, is the sense I get that the multicultural, liberal society (ostensibly advocated by the Archbishop) does not merely tolerate other cultures, but rather expects those cultures to be performed in the public sphere in a way that is palatable to the sensibilities of the tolerant society.